Ask any developer the quickest and hackiest way of locking unauthorised users out of your website and they will probably mention HTTP Basic Auth. As an extremely simple method of authentication that is built-in to the HTTP protocol standard and supported by every web browser, it’s the universal, go-to method of setting up a username and password authentication prompt with minimal work.

Simplicity and minimalism of course bring with them compromise, and most things you may associate with authentication systems cannot be achieved easily or at all with HTTP Basic Auth, so you would probably not consider it your primary authentication method for anything but the most basic of needs. But for our needs, it’s the perfect method of stopping casual snooping and accidental usage of a non-live system.

We’re building a new SaaS product, and we have both a staging system (which is non-live by definition and where we do a lot of our testing with fake data) and a production system (which will be live once the system is ready to launch, but is currently dormant). The production system will eventually be publically accessible but the staging system is only for internal development. Securing both of these systems from outside access during development is a great use case for HTTP Basic Auth.

How this works with Fargate

There are usually two ways to implement HTTP Basic Auth – either on the web server or in the application itself. Implementing in the application does mean you don’t need to fiddle with infrastructure, but it adds more overhead to the application and can make things slower for large numbers of requests. The preference is to add the configuration at the web server level.

However, with Fargate, we have no access to the underlying web server or any of the related infrastructure, and we don’t want to start adding cruft into our application.

Luckily for us, Lambda functions are the perfect, lightweight option for running small functions a large number of times. Lambda@Edge, a specialist type of Lambda, replicates your function to all CloudFront edge locations around the world, allowing it to sit in front of requests to the CDN and run blazing fast.

We can use a Lambda@Edge function in conjunction with our CloudFront distribution to control access to our Fargate-backed application by using HTTP Basic Auth.

Creating the Lambda@Edge function

Let’s start by creating the function that will run with each request. This function will read and set the appropriate HTTP headers to control access using HTTP Basic Auth. We’re using JavaScript here with NodeJS:

'use strict';

exports.handler = function(event, context, callback) {

// Get request and request headers

const request = event.Records[0].cf.request;

const headers = request.headers;

// Configure authentication credentials

const authUser = '***your-username-here***';

const authPass = '***your-password-here***';

// Construct the HTTP Basic Auth string

const authString = 'Basic ' + new Buffer(authUser + ':' + authPass).toString('base64');

// Require HTTP Basic Auth

if (typeof headers.authorization == 'undefined' || headers.authorization[0].value != authString) {

const body = 'Unauthorized';

const response = {

status: '401',

statusDescription: 'Unauthorized',

body: body,

headers: {

'www-authenticate': [{

key: 'WWW-Authenticate',

value: 'Basic'

}]

},

};

callback(null, response);

}

// Continue request processing if authentication passed

callback(null, request);

};

The function starts by getting the HTTP headers from the CloudFront request. It then constructs a string using the hardcoded username and password that we want to authenticate against. Finally, it checks to see whether a username and password has been provided, and if so, whether it matches what we expect.

If nothing is provided, or the credentials are incorrect, the standard WWW-Authenticate header is served to prompt the browser to ask the user for credentials. Otherwise, the request continues uninterrupted.

Defining the Lambda@Edge function

Now we have a function, we need to define it and upload the function to AWS.

resource "aws_lambda_function" "http_basic_auth_lambda" {

provider = aws.us-east-1

filename = "packages/http_basic_auth.zip"

function_name = "http_basic_auth-lambda"

handler = "http_basic_auth.handler"

role = aws_iam_role.lambda_role.arn

description = "Provide HTTP Basic Auth"

runtime = "nodejs12.x"

source_code_hash = filebase64sha256("packages/http_basic_auth.zip")

publish = true

}

The function itself is contained in a file called http_basic_auth.js. This file name is important since the handler name (http_basic_auth.handler) is based on the filename and the name of the exported function inside it.

In order to upload the function to AWS, we need to compress it inside a zip file. On upload, the zip file is automatically uncompressed. This zip file is referred to in the definition.

One last thing to note is that we’re creating this function in the us-east-1 AWS region. This is important since all Lambda@Edge functions to be used with CloudFront must be in this region. The knock-on impact of this is that CloudWatch logs for this function will also reside in that region rather than whatever other region you may be using for the rest of your infrastructure.

Linking the Lambda@Edge function to the CloudFront distribution

Now that we have a Lambda@Edge function, we need to tell our CloudFront distribution to use it for each request. In a previous blog post, I showed a sample CloudFront distribution definition for assets. We’ll use something similar here and add in a link to the Lambda@Edge function:

resource "aws_cloudfront_distribution" "cloudfront_cdn" {

...

aliases = ["www.example.com"]

default_cache_behavior {

allowed_methods = ["GET", "HEAD", "POST", "PUT", "DELETE", "OPTIONS", "PATCH"]

cached_methods = ["GET", "HEAD"]

target_origin_id = "www-origin"

viewer_protocol_policy = "redirect-to-https"

forwarded_values {

query_string = true

headers = ["Host", "Origin"]

cookies {

forward = "all"

}

}

lambda_function_association {

event_type = "viewer-request"

lambda_arn = aws_lambda_function.http_basic_auth_lambda.qualified_arn

}

}

origin {

domain_name = ["alb.example.com"]

origin_id = "www-origin"

custom_origin_config {

http_port = 80

https_port = 443

origin_protocol_policy = "https-only"

origin_ssl_protocols = ["TLSv1.1"]

}

}

...

}

The interesting part of the definition above is the lambda_function_association block. This block associates a Lambda@Edge function with the distribution. This function is run for every request and receives a copy of the request headers.

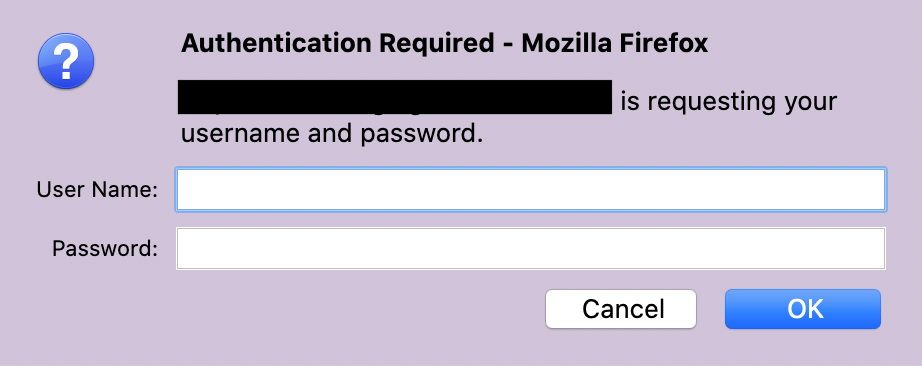

That’s it! Once that’s all built, test it out by visiting the URL you’re protecting. You should see a prompt similar to this:

Test it out by typing a random username and password, and you should be prompted again. Now, try the username and password you previously hardcoded into the Lambda@Edge function, and you’ll see your site.